|

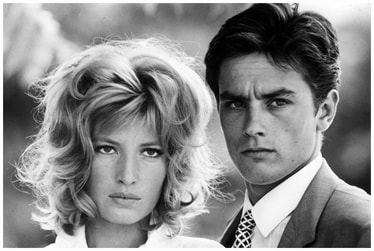

Directed by Orson Welles. Written by Orson Welles & Oja Kodar. Featuring John Huston, Peter Bogdanovich, Oja Kodar, Robert Random, Susan Strasberg, Joseph McBride. by Joseph E. Green Joseph McBride relates in his book Orson Welles a story from the filming of the new Netflix release The Other Side of the Wind, a project he was involved in for six years. In the instance described in his book, the cast and crew had just completed an indoor shot when break was called. Everyone went outside. In McBride’s words: “As the door was rolled back, revealing a brilliant orange sunset over the Hollywood skyline, Welles stared at the natural spectacle outside, took the note of the oohs and aahs around him, and muttered to himself, ‘It looks fake.’” (202) Exactly right. The Other Side of the Wind is so unique in its creation and its unlikely revival by the streaming giant Netflix that the story threatens to overshadow the film itself. And the unique method of its construction also complicates what is already a complicated production. So let’s begin at the beginning. The film has essentially two main narratives. The first narrative is a kind of faux-documentary about the last day of Jake Hannaford’s life, a Hollywood motion picture director (played by John Huston) who was once acclaimed but now has trouble getting funds for his movies. He is having a birthday party and has invited a large group of people to his home. This narrative is captured on all sorts of film cameras, variably in color and black and white, and on different formats. The second narrative is the film that this director has been making, in an effort to appeal to contemporary audiences. The conceit is that the people at the party are screening this new film. Some of the execution of these scenes suggests Woody Allen’s film Stardust Memories, although it seems unlikely he would have seen any of the Welles picture in the late Seventies. Still, there are echoes.  A scene from ZABRISKIE POINT A scene from ZABRISKIE POINT Many of the characters shown in the film have real-life analogues, including Huston playing some version of Welles himself. Producer Robert Evans, film critic Pauline Kael, and many others are represented; and, indeed, the film-within-the-film is another representation – primarily evoking the style of the director Michelangelo Antonioni. That film, also called The Other Side of the Wind, stars Oja Kodar and Robert Random as young beautiful people who follow each other through ominous expressive settings as a prelude to sex. Antonioni had first found fame through a picture called L’Avventura, which screened at the Cannes festival and drew praise and boos in roughly equal measure. A sedate, languid film, the film tells a story of a woman who disappears and the search – more or less – for her by her ‘friends.’ I personally find the film fascinating, but understand why others disagree. The same is true for other Antonioni films, such as L’Eclisse, Red Desert, La Notte, and Blowup. However, Welles took special aim at Zabriskie Point, a picture which even Antonioni’s most ardent fans (such as myself) will not defend with much vigor. Welles, in fact, shot much of his film in a house adjacent to one that Antonioni had blown up in Zabriskie Point. In Orson Welles’s Last Movie: The Making of The Other Side of the Wind, author Josh Karp notes that “…the world Antonioni created on screen bothered Orson to no end. Because while Welles tangled with love and hate, life and death, and the unknowability of man, Antonioni’s films were about existential ennui with characters who lived empty lives covered by another layer of ennui. It defined all that Welles despised about the auteur theory.” (64) In an Orson Welles film, the characters are all very strong personalities, with clearly defined goals and principles – although they may fail, and indeed Welles may find that emptiness lies at the end of the striving, there is striving. Charles Foster Kane may wind up a recluse wishing for his childhood toy, but a burned-out torch once had a fire. Antonioni’s films are not characterized by fire. The characters in Antonioni films often carry around thousand-yard-stares of blank affect, paralyzed by the neurosis of modernity. His greatest ingenue, Monica Vitti, most often presented no expression whatsoever. Indeed, in Antonioni’s most famous film, Blowup, a photographer (David Hemmings) who specializes in capturing reality finds that he cannot trust reality – and is only moderately distressed by the discovery. In the end, he decides to shrug and play along.  Monica Vitti with the great Alain Delon from L'ECLISSE Monica Vitti with the great Alain Delon from L'ECLISSE As Joseph McBride noted in my recent interview with him, however, it is interesting to note the similarities between Antonioni’s own La Notte and The Other Side of the Wind. Both films take place during a party, over the course of one night, and partly around a pool. The screenwriter William Goldman once observed that he spent a very enjoyable evening listening to film students discuss water images in La Notte. Perhaps Welles had been influenced a bit, even by his aesthetic enemy? Perhaps. But that leads us into one of the subjects of this complex film: Welles’s relationship with the critical public. In The Other Side of the Wind, Jake Hannaford (Huston) is beset by hangers-on, old friends, old enemies, and photographers. He does most of his communicating through a protégé, Otterlake, played by Peter Bogdanovich, who serves to blockade somewhat the most inane questions – such as when Mister Pister (McBride) asks him if his “…camera is merely a phallus.” The trouble is, however, that Hannaford hasn’t had a success in a long time, is having trouble making the bills, and his legend – running on fumes by this point – only survives through those fans and film scholars. Or, as put by one of many quips that zip by at the party, “You wouldn’t know a cineaste from a hole in the ground.” Hannaford, we are told, is the “Ernest Hemingway” of filmmakers, although what at first sounds like a compliment begins to sound like tragedy by the end. He is a man out of time. We watch him watching his own film with drunken indifference and perhaps bewilderment. At one point the projectionist complains that he’s showing the reels out of order. “Does it matter?” Hannaford asks. Gradually we find out it does not. He’s in dire straits. His leading man bolted from the production. The money’s gone. And then, in one of the most powerful scenes, he goes to his last resort: attempting to borrow money from his protégé, Otterlake, who declines. Inevitably the scene echoes a Henry-Falstaff relationship, as the betrayal plays out. “The forty million that was mentioned…” he starts to say, but Hannaford interrupts him: “I know kid, let me finish the line for you. It’s still a distant hope. How’s that for dialogue?” Otterlake, taken aback, then responds: “What did I do wrong…Daddy?” This seems to have been a preoccupation with Welles’s later years, as Joseph McBride points out that in the film F for Fake, Welles also explicitly mentions Falstaff and Henry in connection to the hoaxer Clifford Irving, who exposed the forger Elmyr de Hory. McBride then connects Welles’s identification of the Irving-Hory relationship with Mr. Arkadin and the protagonist’s relationship with his “…biographers, who expose his guilty secrets to the world.” (182-183)  Bogdanovich & Huston Bogdanovich & Huston And so the son must kill the father. Bogdanovich, in his book Who the Devil Made It, relates a story about Dennis Hopper at a small dinner party in which the classic Hollywood director George Cukor (The Philadelphia Story, A Star is Born) was also present. Hopper made a point of telling Cukor, “We’re going to bury you, maaaan.” Cukor politely responded, “Well, sure. I’m sure.” Hopper, who has a small role in The Other Side of the Wind (typecast as partygoer on a drug trip) broke apart all the old Hollywood rules with Easy Rider, ushering in a world that Hannaford only half-heartedly tries to keep up with in his film. This crossing over between the “real” world and the picture happens in virtually every scene, lending depth and shading to the proceedings. It also makes this a picture for film buffs – the same “pests” that Welles complains about during the course of the film are also his chief audience. And finally the construction of the film means that it echoes both films of the past and the future in strange ways. So while it is possible to see the influence of Godard and Antonioni, certain scenes also seem like influences (although they can’t be!) on films as diverse as William Peter Blatty’s The Ninth Configuration and Oliver Stone’s JFK (particularly in some of the black and white montage sequences). The Other Side of the Wind is a postmodern commentary on itself, and is as far away from the perfect-pitch execution of Welles’s early films as imaginable.  The other potential influence on the film – and a question I would love to have answered – is the question of “El Boom.” During the 1960s and 1970s a group of young Latin American novelists broke through to commercial success in America, an event which is referred to as “El Boom.” These novelists – the Argentinean Julio Cortazar (whose short story formed the basis for Antonioni’s Blowup), Gabriel Garcia-Marquez of Colombia, Mario Vargas Llosa of Peru, and Carlos Fuentes of Mexico all seemed to arrive fully formed at once. Their novels were in turn heavily influenced by French literature in particular, but also Jorge Luis Borges, the spiritual father of these novelists to one degree or another. Borges had been a film critic in his youth (one of his reviews was of the original King Kong) and Hollywood had an impact on all these men. The Other Side of the Wind contains many elements reminiscent of these fiction writers, particularly in its overly experimental nature. Cortazar, for example, wrote a novel in which the reader can pick which chapters he or she can read (Hopscotch), and a short story in which a murderer targets the reader of the story. This experimentation was a specialty of Borges as well – in one famous story, a man rewrites Don Quixote word for word, and the temporal distance makes his work a deeper and more interesting than the original. Another story concerns a detective who gets so lost in Hebraic word-puzzles he fails to see his own death prefigured (shades of Blowup). Orson Welles, in this film and F for Fake especially, took to deconstructing the nature of filmmaking itself, just as these writers were exploring the limits of word, story, and novel. However, the novel that kept coming to mind watching the film was A Change of Skin by Carlos Fuentes. The first of the three sections of the novel is titled “An Impossible Feast,” a play on the Ernest Hemingway novel A Moveable Feast, just one of the many pleasing connections. The novel concerns a trip taken by a few characters with conflicting backgrounds, and a betrayal that takes place among them. In one section of the novel, the narrator, Freddie Lambert, invokes memories of the films they used to see: “You don’t remember. I bet you don’t. But we used to know them all. Every afternoon after school we used to go to the movies. Or we would sit in the soda fountain and ask movie riddles, to see who knew the casts best, the cameraman, the other technicians. Yes, we even knew the names of the cameramen. And today the only ones I remember are Tolland [sic] and James Wong Howe…” (132) Tolland refers to Greg Toland, Orson Welles’s cameraman for Citizen Kane. And it just so happens that Fuentes had previously borrowed the structure of Kane for his most famous novel, The Death of Artemio Cruz, published in 1962. In A Change of Skin, the ending takes place at a party, in which actors portraying the characters of the book repeat some of the major incidents of the book – a metafiction in the same way The Other Side of the Wind is a metafilm. The play’s the thing. Was this part of the framework of Welles’s influence? Who knows. One would think he would have been aware of “El Boom,” especially as he spent so much time in Spain prior to 1970. In terms of literature in that period, Latin America was where the action was. Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow wasn’t out until 1973, although John Barth had already put out Lost in the Funhouse by 1968. Meta-narratives were in the air.  Anjelica Huston in THE DEAD Anjelica Huston in THE DEAD Although there is one other story that seems to have been a major influence on the film: The Dead by James Joyce, which also takes place during a party and ends – expressed in some of the most gorgeous prose ever committed to paper – with a kind of betrayal. And a recognition of a passion which is buried, and will remain so, for eternity. John Huston’s last film was an adaptation of The Dead, in 1987. For his part, Josh Karp notes that Orson Welles died in his bathrobe at age 70: “Just like Jake Hannaford.” (236) Paraphrasing Orson Welles, happy endings are all about where you end the story. Joseph McBride mentioned that producer Frank Marshall felt a certain melancholy about The Other Side of the Wind, because death is baked into its very structure, right up until the incredible final sequence of images. McBride disagreed; the film is out; the rest is celebration. Bogdanovich once said to me that “no special effect can compete with the human face,” and this film is a testament to that. The film exists, is available to be seen, and after more than 40 years it’s hard to see this development as anything other than a happy ending.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis is Joe Green's blog. Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed