Patty Hearst & the Twinkie Murders: A Tale of Two Trials by Paul Krassner PM Press, 112 pp., $12.00 by Joseph E. Green "I really lost it that day." -Dan White “Sometimes paranoia is just having all the facts,” William S. Burroughs once said. For his part, Paul Krassner once pointed out to television host Tom Snyder that “conspiracy and paranoia are not synonymous.” In his new book, Patty Hearst & the Twinkie Murders: A Tale of Two Trials, counterculture Hall of Famer* and former Realist publisher Krassner gives us an inside view on two incidents that prove out both those statements. Both were enormous public sensations at the time. The first began on February 4, 1974, when Patricia Hearst, the granddaughter of William Randolph Hearst, (newspaper king and thinly disguised subject of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane), was kidnapped by a group calling themselves the Symbionese Liberation Army. The SLA, led by Donald DeFreeze, traumatized and brainwashed the young college student until she eventually joined them in committing crimes, including a spectacular bank robbery that captured the attention of the country. Eventually the FBI caught up with them, and after a shootout DeFreeze and five others were either shot or burned to death. Hearst herself eluded the police for a while longer before being apprehended on September 18, 1975 in San Francisco. However, as Krassner points out in his rollicking and frequently hilarious prose, there were signs of more than casual government involvement in this one. John Judge always told me to find people who connect one event to another, who pop up on the timeline, linking atrocities. It has served me well. Krassner points us to a certain Charles Bates of the FBI. Bates was an FBI special agent in the Chicago office when Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were murdered in December 1969, but ended up in Washington D.C. in 1971, just in time to be put in charge of the investigation into Watergate the next year. Two years later, in 1974, Bates was placed in charge of the hunt for the SLA and Patty Hearst. (36)

Also interesting can be the locations. Before Donald DeFreeze became ‘Cinque,’ the leader of the SLA, he spent 1970 at Vacaville Prison in California, following a stretch as a police informer for the LAPD. His handler, a man named Westbrook, Krassner notes, worked for the CIA. (18) Vacaville has a notorious reputation, having been named in the mid-1970s in the Senate investigations into MK-ULTRA as a result of the testimony of Dr. Sidney Gottlieb. The prison had been the site of numerous psychological tests on the inmates, some including LSD, going back to the 1950s, when a young Charles Manson also had been incarcerated at Vacaville. Krassner notes that an investigator found that DeFreeze had set up a conjugal visit program while in prison and had received visits not only from future kidnappers but also by Patty Hearst herself, under an assumed name. (32) (Later, Hearst testified that she was "struck by a terrible fear of being kidnapped" just before she was kidnapped.) California congressman Leo Ryan, who had leaked information and spearheaded inquiries into government experimentation, including into the development of Donald DeFreeze, was shot to death while visiting Guyana where he ran afoul of a certain Jim Jones. Jones forms part of the background for the second essay in this book, as Krassner details his experiences sitting in on the trial of Dan White, the man who shot Harvey Milk and George Moscone on November 27, 1978, just a couple of weeks after the Jim Jones Guyana ‘suicides.’ (It should be noted that the Guyanese coroner, Dr. Mootoo, found no suicides had occurred; his report documented them all as murders. See The Black Hole of Guyana by John Judge.) Also, Milk and Jones enjoyed a close relationship right up until their deaths, as demonstrated by their frequent correspondence. The madness of both trials is underscored when Krassner contrasts the sentencing of the two subjects, Patty Hearst and Dan White. Hearst, who had been kidnapped and brainwashed, received 35 years. (This was later commuted.) Dan White, who first murdered Moscone in cold blood (shooting him in the body and then twice in the head, after which pausing to reload) and then walking over the Harvey Milk’s office to shoot him there. White got 7 years. White received such a relatively minor sentence because of the ‘Twinkie defense,’ provided by his attorney Martin Blinder in a phrase that Krassner himself helped to popularize. (71) The defense stated that White had been depressed and eaten too much sugary junk food, which put him in a poor mental state. After the verdict was announced, there was (understandably) a riot in the neighborhood, which resulted in Krassner getting beaten by a cop and receiving permanent injuries that affect him to this day (77-78). When Krassner reports the news, it’s as an eyewitness and participant. Patty Hearst & the Twinkie Murders: A Tale of Two Trials is a must-read for anyone interested in the period, in the dirty realities behind the illusion of large media, or in political research in general. The book is fast, funny, memorable, and sharp as hell; and like all great satire, it makes unappetizing truths easier to swallow. *I don't mean this poetically. There is a Counterculture Hall of Fame, and Krassner's been elected to it. In 2001.

6 Comments

While I was preparing for the Coalition on Political Assassinations meeting last year for the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy murder, a piece was published in the Rivard Report about conspiracy theories. It was written by the self-identified poet Don Mathis, representing St. Philip’s College. I stumbled upon it by accident last week. There isn’t time to respond to every bit of nonsense that propagates on the internet, of course, but being that this came from a local publication and a local college, I decided to spend some time deconstructing it in time for the 51st anniversary. You can read his piece first, titled JFK Conspiracy Theories: “They Didn’t Do It.”

First, one general point: the Mathis piece contains not a single citation or hyperlink as to fact. Without supporting evidence, his entire article is just unsupported rhetoric. As we will see, this is only one of the problems plaguing his chaotic article. INTRO The first three paragraphs concern the author’s desire to “kill” the JFK conspiracy theory and also promulgate a certain misunderstanding of coincidence and conspiracy. To be fair to Mathis, this same confusion is also shared by Skeptic magazine's Michael Shermer, as I pointed out in my first book, Dissenting Views. Coincidence is not literally the opposite of conspiracy, so when the author writes that “It was a coincidence that Jack Ruby was able to kill Oswald,” this ignores Ruby’s agency; i.e., that Ruby wanted to kill Oswald, for whatever reason, and then did so. Ruby didn’t accidentally get into the basement to be in a position to kill Oswald; someone had to let him in, and that someone was almost certainly on the Dallas police force. In the House Select Committee Report on the assassination, Volume 9, there is a detailed report on Jack Ruby’s ties to local Dallas police. It acknowledges his closeness to the police, that he paid for their drinks at his nightclub, paid off certain city officials when he first arrived in Dallas, and was a police informant, as confirmed by interviews with street officers despite Chief Curry’s disavowals. Ruby, while in police custody, said many odd things regarding his motive for killing Oswald, but he also plainly was a conspiracy theorist himself: Chief Justice WARREN. Mr. Ruby, I think you are entitled to a statement to this effect, because you have been frank with us and have told us your story. I think I can say to you that there has been no witness before this Commission out of the hundreds we have questioned who has claimed to have any personal knowledge that you were a party to any conspiracy to kill our President. Mr. RUBY. Yes; but you don't know this area here. Chief Justice WARREN. No; I don't vouch for anything except that I think I am correct in that, am I not? Mr. RANKIN. That is correct. Chief Justice WARREN. I just wanted to tell you before our own Commission, and I might say to you also that we have explored the situation. Mr. RUBY. I know, but I want to say this to you. If certain people have the means and want to gain something by propagandizing something to their own use, they will make ways to present certain things that I do look guilty. Chief Justice WARREN. Well, I will make this additional statement to you, that if any witness should testify before the Commission that you were, to their knowledge, a party to any conspiracy to assassinate the President, I assure you that we will give you the opportunity to deny it and to take any tests that you may desire to so disprove it. I don't anticipate that there will be any such testimony, but should there be, we will give you that opportunity. Does that seem fair? Mr. RUBY. No; that isn't going to save my family. BALANCE Mathis then states that while in the 1970s the public’s belief in the conspiracy was almost at 90%, it is now closer to 50%. He was presumably referring to a November Gallup 2013 poll; however, the news report in question states that the high was 81% and at present it is closer to 61%. Following this misstatement are four paragraphs of pure confusion, in which the author conflates 9/11, the Holocaust, and tsunamis in an effort to explain how we demarcate conscious agency from an act of God. However, the thought is badly expressed and ultimately incoherent. “But there are times when we seek a reason for coincidence,” Mathis writes. “We say a tsunami was caused by an act of God. Such a monumental catastrophe can be understood and accepted if we believe there was an omnipotent force behind it. Some philosophers may claim there are no accidents. Some religious folks may say everything happens for a purpose. But discerning minds can recognize the coincidences in everyday life.” What? In an effort to show that conspiracy theories are ridiculous, Mathis then cites two conspiracy theories which are, it must be said, ridiculous: that J.D. Tippit (the policeman allegedly murdered by Oswald) conspired with Oswald and was shot by him either by mistake or by design, and that Tippit was buried in Kennedy’s grave because Kennedy lived through the assassination. Having attended COPA meetings for the last ten years, I’ve heard a lot of theories. I know most of the major authors in this field personally, and I’ve co-produced and co-written a forthcoming documentary on this topic. And I’ve never heard of these theories. Mathis per usual does not provide a citation, so it’s not clear what he is referencing. However, it doesn’t matter. Even if someone out there holds to the theory that Tippit was buried in Kennedy’s place, this is clearly a fringe notion. There are fringe notions in any inquiry. The fact that a few people believe the Earth is flat doesn’t invalidate science. If you pick up a book written in the last few years about the assassination, such as Jim Douglass’s JFK and the Unspeakable, Jim DiEugenio’s Reclaiming Parkland, Joseph McBride’s Into the Nightmare, or Gerald McKnight’s Breach of Trust – just to pick a few of the best – you will not find anything so outlandish or absurd. Instead, these are serious authors going through the evidential record, one that was incidentally helped by Stone’s film JFK, because of the public pressure it created to release documents about the assassination. Mathis writes: “Some conspiracy theorists don’t even provide a motive. Most are doubly contradicted. Generally, they deny all evidence of a lone gunman. Secondly, they cannot prove evidence to the contrary.” Again, I say: What? The author appears flummoxed to put two coherent sentences together, much less apply logic. PRIOR INVESTIGATIONS The next tact taken by Mathis is a little more interesting, because he does at least cite historical events: the 1968 Ramsey Clark panel, the 1975 Rockefeller Commission, and the 1978-79 House Select Committee on Assassinations. Unfortunately, because of his failure to get into specific evidence, he leaves the reader with the wrong impression regarding these investigations. The devil is in the details. Mathis states that all three investigations “came to the same conclusion – that two shots from the same source killed Kennedy.” This is a flat-out lie. The HSCA, based on the audio evidence, posited a second shooter. That was the last official investigation in the Kennedy assassination (as pointed out in Gaeton Fonzi’s brilliant book) and the government concluded a second shooter best fit the facts. The story of the Clark panel is complex, and I direct the reader to an excellent essay by Dr. Gary Aguilar that goes through the various contradictions and problems with the report produced. It should be noted, however, that the report itself was suppressed for an entire year after having been produced, and only came to the light as a result of the Garrison trial against Clay Shaw. Interesting. Even worse, when the Rockefeller Commission finished its final documents, it misreported one of the experts, Dr. Cyril Wecht, as agreeing with the findings (of all shots from the rear) and buried their report for 23 years. Only in 1998 were Dr. Wecht’s complaints about how his testimony was used vindicated. Why would suppression like this be necessary if there were no covering up going on? What is the point? A couple of paragraphs down, Mathis lies again. He makes the usual claims about “conspiracy theorists” inventing bogeymen for psychological reasons. But then he writes: “But in the 50 years since the assassination, no one has admitted being part of a conspiracy.” Not only is this false, it was false before the assassination even happened. Richard Case Nagell, a CIA operative, learned of the plot and arranged to get himself arrested in El Paso in September 1963, two months prior to the murder. He then warned authorities of the coming assassination although he was ignored. He was also ignored by the Warren Commission, despite the existence of an FBI memo from December 1963 that states Nagell was confirmed to have met with Lee Harvey Oswald in Mexico and Texas prior to the assassination. The full story can be found in Dick Russell's The Man Who Knew too Much. Now Nagell is hardly the only person to have come forward; many people have over the years, and their credibility has to be assessed one on one, with respect to the evidence. Watergate criminal and CIA operative E. Howard Hunt, for example, made a deathbed confession that was widely publicized -- although, like anything else, we have to evaluate it on its merits. However, simply glossing over the mountain of information available to the public is ridiculous. FINAL REMARKS Mathis invokes an ABC special in which Dale Myers purported to prove the viability of the single-bullet theory. Ironically, his endorsement of Myers’s 3D fantasy arrives in the same paragraph dismissing Oliver Stone’s JFK, which was so powerful it stirred the government to release millions of pages of documents as a response. With reference to Myers, it should be understood that a computer simulation only means something if the correct parameters are set ahead of time in the program. Basically, a simulation will show you whatever the person using the simulation wants to show you. The issues involved are somewhat arcane for the general reader, but for a detailed explanation of his methods, see Joe McBride’s superb article at CTKA or his book. We are now 51 years past the Kennedy assassination, and the government continues to this day to withhold documents from the public and has, indeed, been re-classifying previously released documents. Why? What possible national security threat could rest in Lee Harvey Oswald’s still-classified IRS records? Why is the CIA fighting Jefferson Morley’s FOIA suits requesting the records of George Joannides, potentially a key figure in the assassination? Why would the Rockefeller Commission bury the comments of Dr. Cyril Wecht for 23 years? This is not a question of being a “conspiracy theorist.” This is a question of asking hard questions of our government, which is part of the responsibility of living in a democratic republic. Oliver Stone’s JFK released in 1991 and became the highest grossing film of that year. Its success, however, was met by a hostility unprecedented in the major media, with an early draft of a leaked script coming under criticism months prior to the movie coming out. The entire script, with several essays both pro and con regarding the film, were collected in JFK: The Book of the Film, by Stone and Zachary Sklar (see the LINKS page on this site) and it is highly recommended if you are interested in the case.

When I saw it, I was still in college where I had been a philosophy major. I had always been interested in film, especially foreign films, and during the 1980s I would go to the local VHS tape video store and rent pictures that I had read about in film books, such as Aguirre the Wrath of God, Band of Outsiders and Blowup. Most crucially, however, I had grown up the son of a history professor, and spent the formative years of my youth living in on-campus housing at a university in Laredo, Texas. The result was that I spent many days in the college library, had access to a huge number of books, and had grown up with a kind of academic mindset. The reason I bring this up is that it affected my viewing of JFK in a way that may prove instructive. First, I’d like to make two general points about the academic mindset. The first point is that one of the ways university professors survive and obtain tenure is by acquiring a unique sandbox. That is, they find a particular specialty and become the expert in that specialty through long hours of dedicated study. In some ways that is a good thing; the universe is a big place, with an infinite number of topics that cannot all be covered by a single person, so the piecemeal assignation that goes on is helpful toward a goal of general knowledge. When the AIDS epidemic first hit, many of the top scientists who ended up working in the field of AIDS had backgrounds in veterinary science. That’s because the first cases involved cryptosporidium, a disease that had typically only been found in cattle up to that time. The morphology of the AIDS virus (that is to say, what it looked like) is similar to a sheep or cattle virus. In this case, having specialists who had experience in this area proved useful in another area, and this is the sort of the thing that happens all the time. It can also be something that inhibits knowledge. Once the sandbox is acquired, and a person’s personal reputation, livelihood, and status is dependent on that sandbox, a person can be very reluctant to give it up. When the English scientist Bertrand Russell was a teenager, he wrote a letter to the German logician Gottlieb Frege that destroyed his entire system of thought. Frege first denied it, then claimed that “the whole of mathematics is undermined.” Which of course it wasn’t. It’s just that his theory was wrong. He never recovered from this, and we can have empathy for him while recognizing that sandboxes can be as dangerous as they are helpful. The key, as in most things in life, is to remain flexible and adaptable. There’s one more aspect to this sandbox concept. When a professor spends all or most of his or her time in that sandbox, the rest of his or her information about other things tends to stay frozen. They may retain some general knowledge about the rest of the world, but it becomes sketchier and less relevant over time. To their credit, they know this, which is why they rely on experts in their own sandboxes in discussions about areas not relevant to their own. And so everybody is an expert in one thing and vaguely cognizant of everything else. That’s point one. Point two is that there is a specific manner in which academic professors think that can best be captured, I think, with the term categorization. Everything about the university experience is categorized. Art History 101. British Literature 1 and 2. American History is often broken up from the revolution to the Civil War, then the Civil War to the present. And so on, in more and more specific detail. I am not arguing against this. It is natural and right if the desired goal is efficiency. I am only saying that the university professor tends to categorize everything in these terms, including the other professors. (“Well, of course, that’s going to be her argument, she’s a postmodern feminist.”) So a philosophy professor might be a Kant guy or an epistemology specialist or – God forbid because everyone hates this type – a Wittgenstein guy. And you have a certain knowledge and expectation of what that particular type is going to bring in terms of intellectual opinions and objections. And they might be wrong. We are all individuals. But we generalize and categorize, and professors do it more often and more efficiently than nearly everyone. Okay, that’s point two. Now I was heavily influenced by this type of thinking. So, among other things, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise shows the influence of Communist groups in America, for example. Or the great passages about living a natural life in Tolstoy are clearly influenced by Jean Jacques Rousseau. There’s nothing wrong with noting such things, but what can happen is that you create a mental world of wit and reference that folds back on itself without ever impacting the real world. When the Socialist painter Diego Rivera refused to take down a politically motivated mural (which included a portrait of Lenin) at Rockefeller Center, the Rockefellers had the mural destroyed and paid him off in full. They then funded abstract art, possibly for aesthetic reasons, but also because abstract art can only reference itself and cannot carry political messages. One of the most famous museums in America, MOMA in New York City, was built by the Rockefellers. It isn’t just art, either – music also shows a steady progression into abstraction and self-reference, and arguably film does as well. So I saw JFK. And I thought it was excellent. I thought the montages were brilliant and the performances superb. I agreed with Stone’s casting of Kevin Costner in the lead, seeing in him a kind of Gary Cooper-Jimmy Stewart solidity with which to revolve all the other eccentrics. I thought the story was tremendously interesting and thought-provoking and went back and saw it again. However, during all that time, it never occurred to me to think of the conspiracy it depicted as something real, or as something to be taken seriously on a human level. I treated it as a categorizable point of view; that is, the film is an example of an artistic talent demonstrating a certain take on historical events. It’s a Conspiracy Thriller. And although intellectually I understood there was a real debate going on under the surface, I treated the whole thing as an abstract and went back to reading about other things. It would be another ten years before I ever studied the case in detail. Now maybe I’m just stupid. It’s certainly possible. But one thing I know happened is that my academic training prepared me to slot certain ideas in certain categories which ended up being a substitute for real thought. I just never asked the question, the behavior that pains Jim Garrison (Costner) in the film when he yells at the Warren Report: “Ask the question! Ask the question!” For a long while, I didn’t. Fortunately, many others did. Most of them weren’t academics, although a fair number of researchers do come out of university jobs. It’s still a dangerous thing to get into, and one risks both status and livelihood by writing seriously about it. Michael Parenti’s career has been dotted with troubles for being both a committed Marxist and for writing about politically controversial issues his whole life, despite having published numerous books and being much in-demand as a speaker and commentator. It’s not easy. As far as JFK went, however, for whatever flaws one wishes to assign to it, it played a real historical role in the creation of the AARB and the release of millions of JFK-related documents to the public. Not bad for a movie that was excoriated by the mainstream press long before it ever showed up in theaters. It remains a great film and a solid entry point for interested people. Rat’s Nest: Two Books on the CIA-Nazi-drug Nexus by Joseph E. Green

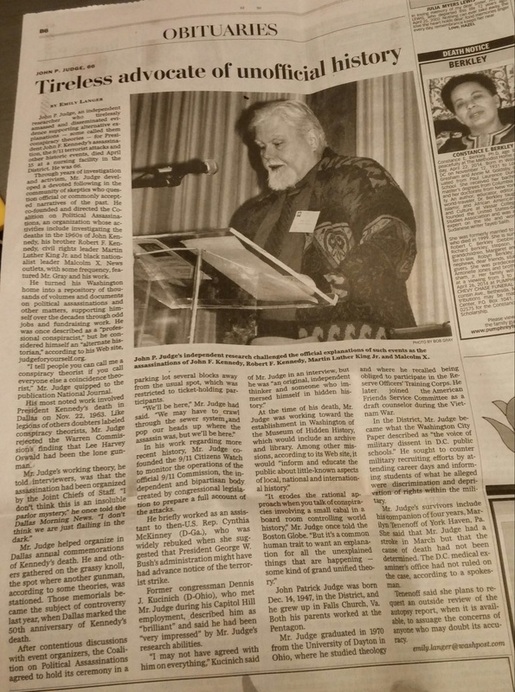

The Essential Mae Brussell: Investigations of Fascism in America edited by Alex Constantine Feral House, 359 pp, $18.95 Drugs as Weapons Against Us by John Potash Trine Day, 420 pp, $18.60 It was a masterstroke of Quentin Tarantino’s film Inglorious Basterds to make a point of Nazi flight in the wake of a losing war. Lt. Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt), after learning that a Nazi captive is going to burn his uniform and never wear it again, informs him: “Yeah, we don’t like that. We like our Nazis out in the open,” right before carving a swastika into his forehead. Then, in the immensely satisfying end of the film, Aldo does the same to Colonel Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz), an officer who has made a deal to ensconce himself into the loving arms of the U.S. military. In the opening scene, Landa describes the Jewish people as rats; but in the end, it is Landa who is the rat, scrambling to desert the sinking Reich. In watching the film, I recognized that the ending might be more satisfying for me than for some others, because many people do not know that Nazi officers and scientists flooded into the U.S. after World War II or how much influence they had over our history. Following the “good war,” the Pentagon and the CIA seemed hell-bent on giving cover to as many Nazis as possible. Some of them went into the U.S. Army historical division (the person who wrote the official Pentagon history of World War II was an official historian of the Reich) and others were scientists who would hold the chief positions at NASA and elsewhere for decades yet to come. One character who did escape to America after the war was Reinhard Gehlen, where he became a willing instrument of the military establishment’s desire for a Cold War. CIA Director Allen Dulles funneled over $200 million to Gehlen. The idea was that Gehlen would use his old contacts to set up lines of information against the Soviets, while also training mercenary forces to fuel revolutionary movements with Russia. (Does this sound familiar?) Indeed, the CIA itself (which was created in 1947) was largely a combination of the old OSS (Office of Strategic Services) and Gehlen organization members. (Brussell 61) Additionally, as Mae Brussell notes in a new collection of her work put out by Feral House, “Some of [Gehlen’s] spies were schooled at the CIA’s clandestine base in Atsugi, Japan, where, in 1957, a young Marine named Lee Harvey Oswald was posted to the U-2 spy plane operation there.” (Brussell 23) Mae Brussell has been described as the Queen of Conspiracy numerous times, which is a belittling nickname even if not expressed with such intent. She was, instead, one of the most brilliant intuitive thinkers who ever lived, and legendary at analysis. I never met her, alas, but heard many stories about her from my friend John Judge, as she and Penn Jones were his mentors. And while recordings of Mae are easy to find (the best collection can be accessed at www.worldwatchers.info, along with other Mae-related material), print has been rare. This new collection, edited by Alex Constantine, contains her most well-known pieces and examples of her prodigious facility. Having the book in print is also nice for those who wish to slowly digest the material, as listening to her radio shows can be challenging for the uninitiated as she zips from topic to topic. What Brussell specialized in was milieu. She figured out who the players were in any situation she investigated, then who was related to whom, and who was connected to whom, and eventually she revealed the dark tunnels underneath the American dream. As she discovered, the fascists rule in secret while our Punch and Judy “democracy” keeps people distracted. Her ability to analyze events this way made her prescient, as when she warned Mary Jo Kopechne’s family that she was about to be killed shortly before Chappaquidick, or even writing a warning letter to Richard Nixon. There are other observations sprinkled throughout the book with deep consequences. For instance, she mentions in passing that Clay Shaw, the subject of the Garrison trial and the later Oliver Stone film JFK, happened to die a few weeks after being publicly outed as a CIA asset in Victor Marchetti’s The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence. (B 115) Like Penn Jones, Brussell did a great deal of work on suspicious deaths, and the timing of such deaths. She also observed that Hale Boggs, a Warren Commission member who expressed doubts about the final report’s conclusions, died one month after the Watergate arrests were made, in a plane crash. According to a Los Angeles Star story, she points out, Boggs was planning to make public links between the Kennedy assassination and Watergate. (B 113) Brussell also wrote astonishing exposes of CIA operations such as the Symbionese Liberation Army’s kidnapping of Patty Hearst, which occupies a large section of the second half of the book, and even the deaths of West Coast rock and roll stars. As she points out, the two biggest bands of the era became associated with murder and hate – the Beatles via Vincent Bugliosi’s ridiculous conspiracy theory regarding Charles Manson, and the Rolling Stones via the Hell’s Angels murder of an unstable fan during the Altamont concert. (B 277) What is the purpose of all these intrigues? She relates it to the underlying white power structure. As she puts it: Competition for jobs between Indians, Blacks, and Chicanos is caused by a racist power structure in this country that refuses to allow jobs in the first place…IQ tests have been proven to be racist, thereby dropping off otherwise qualified students. By keeping minorities out of the professions except entertainment and athletics, the white community can keep their residential areas white, their schools white, their churches white, perpetuate the racism. (B 133) Despite the articles in this book being decades old, none feel out of date. They feel more relevant than ever. Indeed, what has happened is that the power structure has gotten better at it. They’ve turned pro, both in a raw political sense but also in a cultural sense. The list of musicians that Brussell talks about is sobering: Hendrix, Joplin, Morrison, Phil Ochs, Gram Parsons, Lennon, and Otis Redding, among others. Is there anyone on the current cultural scene of that quality and impact? The obvious answer is no. When Lennon looked like he was getting ready to re-enter the mainstream, he was gunned down by another lone nut, which America seemingly specializes in producing. In response to this, Brussell has the single best advice I have ever read about such murders: When someone is gunned down who is controversial, has political enemies, is hated by the wealthy and well-organized religious movements, and is an open opponent of government policies at home and abroad, that kind of murder requires much more inquiry into the background of the assassin. (B 284) Exactly. As if to prove the timeliness of Brussell’s observations, a new book – Drugs as Weapons Against Us by John Potash – will be coming out in November on Trine Day. Potash, who previously authored The FBI War Against Tupac Shakur, states in his book that he is building on the work of other researchers such as Peter Dale Scott, Brussell, and Constantine, the editor of The Essential Mae Brussell. There is a slight difference in focus as explained by the title Potash gave to his work, but it fits snugly alongside in terms of the research and point of view. Potash tackles a broad spectrum of topics that converge on the topic of drugs, with an emphasis on the 1960s to the present. He first sets out some of the historical background of the opium wars and then quickly gets into government experimentation and abuse of mind-altering chemicals. And it’s here that Potash may create some controversy with readers of his book: he doesn’t support marijuana use or LSD use for mind expansion. As he points out, the CIA used the latter for purposes such as disorientation and truth extraction, but not for achieving higher levels of consciousness (Potash 32). He even quotes William S. Burroughs, famed author and heroin addict, as saying “LSD makes people less competent.” (P 37) The book also suggests that Ken Kesey and Tim Leary may have been (unknowingly?) doing the government’s bidding in promoting drug use. Kesey himself actually participated in an MK-ULTRA (mind control) experiment in 1960. In describing the Magic Bus, Potash notes with interest several people connected to it who had military and/or blueblood backgrounds, and whose primary function seemed to be financing and encouraging figures such as Neal Cassady and Kesey. Further, what would somebody like the CIA’s John Gittinger be doing at Acid Test parties featuring the Grateful Dead? How did the Grateful Dead break out of the San Francisco scene to become a national success? The answers are both convoluted and fascinating, and in the book. Drugs as Weapons Against Us gradually throws up a pattern constituting a street-level cultural war. COINTELPRO went after movements like the Black Panthers and targeted individuals like Dr. King and Malcolm X; at the same time, the CIA infiltrated the music scene. Many people find this difficult to believe – why would government forces be interested in someone like Jimi Hendrix, for example? Scotland Yard claimed to quote Hendrix’s attending doctor, Dr. John Banister, saying Hendrix was ‘dead on arrival…[dying] in the ambulance or at home.’ The ambulance workers denied this. The hospital’s official report had Hendrix’s hospital arrival time as 11:45 and pronounced dead at 12:45. [Monika] Danneman claimed Hendrix was alive when the ambulance workers took Hendrix from their apartment. If Hendrix was dead on arrival, what happened during that hour? Scotland Yard couldn’t give Danneman an answer. When she asked what Dr. Bannister had to say about it, Scotland Yard told her that he had been struck off England’s official medical register of all doctors in the country, without any further explanation. (P 145) At the same time, Hendrix’s manager, Mike Jeffery, had connections with the Mafia and FBI and had formerly worked for MI6, Britain’s intelligence agency. (P 146) There is more, a great deal more, and the devil is most certainly in the details. It’s an incredible story, but just one of a hundred in Drugs as Weapons Against Us. Potash also takes us through the attacks on hip-hop artists, Panther leaders, Bob Marley, and in a startling set of chapters, the murder of Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain. He also brings us up to date by describing how an unknown party dosed people with acid at Burning Man events and comparing it to the Grateful Dead’s long association with LSD. It is literally true that the year after Jerry Garcia died and touring stopped, LSD use dropped considerably in the U.S. “Slate magazine writer Ryan Grim wrote, ‘For 30 years, Dead tours were essential in keeping many LSD users and dealers connected, a correlation confirmed by the DEA in a divisional field assessment from the mid-1990s.’” Fortunately for LSD dealers, the band Phish entered the gap to help keep their business rolling. (P 281-283) The extraordinary scope and detail in Drugs as Weapons Against Us makes it difficult to summarize. Readable, compelling, and packed with stunning information, Potash’s book works both as a terrific introduction for the beginner and an excellent resource for the veteran researcher. It serves as a kind of textbook to modern American history, covering all the aspects history books typically ignore. Taken together with the Brussell volume, these are vital and necessary defenses of the mind against the idiotic, and sinister, propaganda fed to us daily by major media.  It was mid-morning under grey skies somewhere between Dallas and Waco, on our way to the Poage Legislative Library at Baylor University. Randy Benson, a filmmaker and professor of documentary studies at Duke, walked alongside me. We trailed two figures walking and talking beside each other: John Judge and Robert Groden. “This is like being a hockey fan,” Randy said, “And we’re hanging out with Mario Lemieux and Wayne Gretzky.” I agreed. We all walked into Starbucks and grabbed a table. I had met all three men during a trip to Dallas in November for the Coalition on Political Assassinations conference. I had decided to go after encountering an article by John Judge called “The Black Hole of Guyana” in a book called Secret and Suppressed. It impressed me because – in the first place – the information was incredible. It told a story of the Jim Jones cult suicides utterly at odds with what was conventionally known. No Kool-Aid to be found here. Secondly, however, was the thoroughness of the documentation Judge had used. It was scholarly. It used Guyanese sources rather than standard Western sources, which told a far different tale. There were no suicides at Guyana. The autopsist, Dr. Mootoo, had ruled all of the dead to have been murdered. I had become interested in so-called “conspiracy literature,” which was fascinating but often ill-documented. All too often large claims were based on singular testimony or dubious provenance, so that they didn’t always pass rational muster. I was struck by the emphasis on detail and care that went into the article’s sourcing. Not long after hearing about the COPA conference and seeing that it was up the road from me in Dallas, I decided I had to meet him. That first conference I arrived early – about 10 AM – at the Hotel Lawrence, a rickety building with two elevators, one frequently inoperative, but conveniently close to Dealey Plaza. I went up to the 2nd floor breakfast room and saw John sitting at one of the tables, going through some papers and having his breakfast. I walked over, tentatively. “Hi,” I said. “I’m Joe. I know you’re, uh, John Judge. Mind if I sit down?” He agreed and three hours later we parted company and said we would talk later, after the night’s speakers. I remember going outside in a bitter wind, barely feeling it because my mind had been blown in so many directions. I had received my first taste of the John Judge experience. Talking to John could often be like drinking from a firehose. (WAIT, what did he just say?? And then what?? And wait a minute – what?!?) He flowed from one astonishing fact to another so fast that you couldn’t keep up. He had become a researcher via his own mentors, Mae Brussell and Penn Jones, and adopted some of that style for his own. I’d get better keeping up, with practice. Through John at the conferences I met Robert Groden. Groden was a legend – the man who brought the Zapruder film to popular consciousness along with Dick Gregory on the Geraldo Rivera program, Oliver Stone’s research expert on the film JFK (and who had played several roles in the film), author of High Treason and The Search for Lee Harvey Oswald and creator of the rotoscoped version of the Zapruder film. Which is why Randy made his remark to me. And it was true – a bit astonishing to be chatting mildly over tea and coffee in some tiny Texas town. This would become a typical COPA experience. I attended every COPA conference in Dallas after that, and became more and more involved with the setting up (always to John’s specifications) and helping with whatever needed help. In 2008, COPA held conferences in Los Angeles (to mark RFK’s death) and Memphis (for Dr. King), which is how I ended up complaining in solidarity with Bill Turner about our LA hotel and having the singular experience of Judge Joe Brown buying me barbecue and listening to stories about the Black Panthers and skiing in Colorado. It is hard to overestimate how amazing the conferences were, in terms of being able to sit around and pick the brains of so many high-level scholars. And it was always brilliant to find that someone you knew had written a book, like T Carter with her A Memoir of Injustice, or to find a researcher you immediately hit it off with, like Shane O’Sullivan or John Potash. And naturally over the years John and I became friends, and he served as a mentor in many ways, helping to guide me through the thickets. My first book, Dissenting Views, was dedicated to three people: Ben Rogers, the archivist for the Poage Library, Jim DiEugenio for publishing many of my articles (including my first, “The JFK 10-Point Program”) and to John, precisely for his stewardship. I could always check my thinking with him, see if I was on the right track, and though I didn’t always agree with him I always respected his agility of mind. *** I am sitting on many years of emails, on a huge variety of topics political, philosophical, and personal, and what shines through in them is his warmth of feeling, his humanity, and his wicked sense of humor. On the phone, I became accustomed to hearing his standard greeting for me: “How are ya, Doc?” or sometimes a booming “Doctor Green, the younger!” (My father is a professor and I grew up around academia, and John always granted me an honorary Ph.D.) And then we’d be off and running about one topic or another. A few years ago, John met a girl. On an internet dating site. And suddenly our conversations changed, and I found myself listening to him wax poetic about a certain Marilyn he’d met and how he wanted me to meet her. The idea is a bit astonishing – looking for a date on a website and finding John Judge. But that was John; human, after all, not a walking encyclopedia, a real live person. And he was a happier man for that. Running a conference isn’t for the weak. He got a lot of shit. There were idiots in the 9/11 Truther movement who disrupted COPA events and sent nasty emails because John didn’t think the Towers had been destroyed by controlled demolition. They didn’t know that John had worked closely with victims’ families or bothered to understand why he thought the way he did. As always in our thing, there were people who thought he was a CIA agent or FBI informant. I used to tell him, “If you’re working for the CIA, you need to renegotiate your contract, because they need to get you some checks.” We laughed those off, mostly. But putting yourself forward always is a risk, and one he accepted with aplomb (most of the time) and bitchiness (some of the time). He tried to ignore most of the “skunks,” as he put it, but sometimes he couldn’t, as when certain members of COPA perpetually tried to tie their personal events under the COPA banner without telling him, or tried to recruit every nutter in Christendom into the fold. Those are the things that made him angriest, and he often sent me long, blazing emails about such betrayals. However, the times that will stay with me forever are the human ones. Eating dinner with him in Memphis and listening to a story about an out of body experience from his days in Ohio. The one conference speech he gave in ‘09 where he described how dolphins will sacrifice for one another when they know death is imminent for some or all of the group. Getting a call to go up to his room so I could help fix his tie or get his shoes on when he was injured. The late nights with the other techies (Randy, John Geraghty, Tim Plainfeather, and others who came and went) making sure microphones were ready and cameras in place. The one time John yelled at me (because another “tech” person, C—, had screwed up the audio on movie night) and after I fixed the problem couldn’t help thinking “I just got yelled at by John Judge,” and how cool that was. And how we then skipped the movies and went to an all-night restaurant. The conferences were always 24-7 affairs, and I used to get 3 or 4 hours of sleep per night with everything that needed to be done. This led to a certain level of punch-drunkenness by the time Sunday rolled around, but it was worth it. It was a good exercise for the brain to have amazing information given to you during the day with so many brilliant speakers, and then work most of the night getting everything ready for the next day. There have been two conferences in the United States that have been traditional rivals in the JFK community: COPA and Lancer. Many people thought that there were mere differences in opinion between the two, or that it was based on personality disputes. It wasn’t. Those close to the situation know what I mean, but I will say that I never regretted my choice of which entity to support, even when COPA was on a shoestring and Lancer appeared to have money coming out of its ears. Randy and I have since become good friends, and indeed I’ve made many good friends over the years as a result of John and the conferences. We’re both involved in the making of documentaries about the Kennedy case; his, The Searchers, is a brilliant celebration of the original Warren Commission critics. The one I am involved with is still in post-production but features many things, including the last recorded interview with John, which I conducted. It will hopefully be out before the end of the year, but as anyone will tell you it isn’t easy these days. My hope is that both these films will help preserve the memory of John and the causes he stood for, which were much larger than simply JFK. He was an incredible scholar, a wide-ranging activist whose absence is felt in veteran counseling and in DC schools, a dedicated servant to advocates for change like Cynthia McKinney and Dennis Kucinich, and a larger than life figure on the research scene. But for me, mostly he was my friend who I admired. I will miss him, his intelligence, tenacity, and sometimes hilarious-if-dark quips. His goal of creating a Museum of Hidden History is a perfect summation of his ideals. He was on a mission to better ourselves, to see and acknowledge the darkness within us, and to try and pull it into the light. Donations can be made to a gofundme site or to the Museum of Hidden History at PO Box 772, Washington DC 20044. |

AuthorThis is Joe Green's blog. Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed