Actor Duane Jones, star of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. Actor Duane Jones, star of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. Once upon a time, there was a guy who was determined to make motion pictures on his own, without stars or financing. In Pittsburgh. The guy’s name was George A. Romero, and the picture he made was Night of the Living Dead. In this pivotal year, 1968 – during which, among other things, Dr. Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy would be murdered by the forces of American fascism – he cast as his lead a theatre actor named Duane Jones. Jones happened to be African-American. Romero said that he’d won the part by giving the best audition rather than for any other reason. It was nonetheless unusual, and notable, especially in that the character, Ben, was not defined in any way by his blackness, but by his strength of character, intelligence, and command. He is the only character who keeps his head on throughout the picture. The year before, Sidney Poitier had broken taboos in In the Heat of the Night and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Night of the Living Dead has held up better than either of those: Horror is stronger than justice. Indeed, the core of the story has impaled itself into our consciousness so deep that everyone knows what a zombie is, what it does, and what the rules are for its existence. Like so many of Romero’s films, Night of the Living Dead is really about the collapse of civil society. The undead begin to walk, and for a while there is chaos; during the course of the film, we learn that armed posses have begun to surge against the tide of zombies. We also learn that they can be re-killed, but only via burning or a shot to the brain. In the meantime, a few souls barricade themselves from the zombies, led by Ben as he tries to get them to cooperate and not lose themselves to panic. Alas, everything turns to shit, as they tend to do, but Ben manages to survive out the night.

There is a great scene near the end where he is commended by his superior officer. “You’re doing a great job,” he is told. Such a great job that he is being pulled from his station and transferred to another part of the country – where the whole mess is starting again. Hollar’s body language is perfect as he is advised of his fate. One goddamn thing after another. Romero’s films are rough, street level, and present a reality to them that most horror films don’t sustain. He really thinks about how human beings would react to a situation in which zombies became part of the normal course of business. In his masterpiece Dawn of the Dead, he observes a group of four people trying to survive by barricading themselves in a shopping mall. Inside, the zombies do what they did in life: circle aimlessly past shop windows. That reality is established in the opening scenes, where we see a SWAT team descend on a black neighborhood to enforce martial law. Under the strain of the situation, the (non-zombie) residents fight back and the cops respond by shooting people wantonly. It continues when we see groups of rednecks turning the process of shooting zombies into a sport. When our four protagonists arrive at the shopping mall, then are able to drive out the zombies from the building and make a safe haven for themselves. And they set themselves up as a kind of aristocracy: with the mall’s stores of food and clothing, they live in luxury while the rest of the world burns. For a while, anyway. Eventually that world – in the forms of zombies as well as nomadic gangs – comes bursting through the door to destroy them. (Incidentally, Tom Savini, the great makeup effects artist whose work in Dawn and other films came to be celebrated, was originally offered the job for Night. He wanted the job but was drafted into the Vietnam War. Reality intruded.) The best Romero films aren’t high concept, as one might think given his zombie obsession. (In fact, the remakes of his films are fairly effective at the horror bits but disregard the strong characters and themes.) In Martin, a young man believes himself to be a traditional vampire, but who has to resort to razor blades rather than teeth; he later becomes a local celebrity on a radio show where he details his exploits. In the truly bizarre film Knightriders, a group of motorcycle jousters (led by Ed Harris, in his first starring role) attempt to maintain an Arthurian code in our modern age. In Day of the Dead, a military bureaucracy tries to reassert itself in a world that has moved past any hope of control. However, Romero takes these stories in unexpected directions and developing his characters in novelistic fashion, against a backdrop that is both satirical and observant.

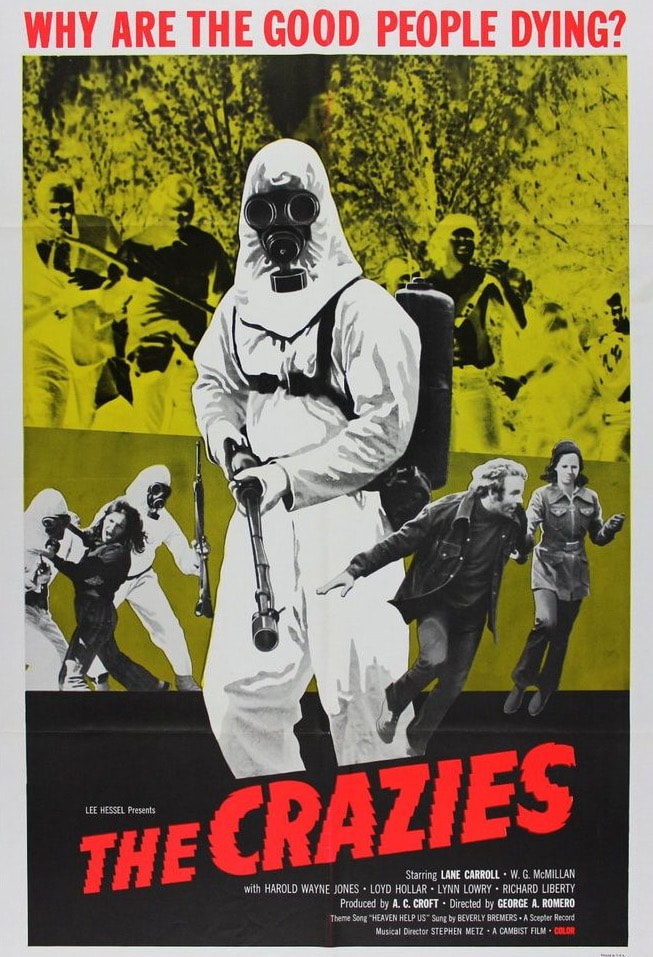

Whether tackling themes of race, sexuality, or most importantly, class – George A. Romero was one of the great filmmakers of his era. Hampered by low budgets and interference (from studios and occasionally his friends), he nevertheless managed to make highly personal films. The monsters and mayhem may have overshadowed that – the people he most directly influenced have replicated his gore but not his thoughtfulness – but in some ways he was closer to John Cassavetes than Lucio Fulci. His pictures were hugely influential on my work, especially my plays, and I will miss him and his work.

George, RIP. Or come back if you prefer.

0 Comments

|

AuthorThis is Joe Green's blog. Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed