|

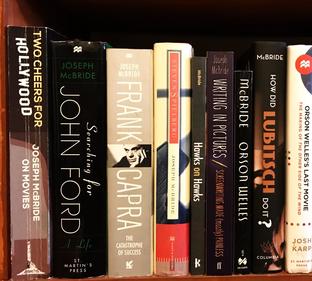

Joseph McBride on Orson Welles and The Other Side of the Wind  by Joseph E. Green Once upon a time there was a young man from Wisconsin who flew out to Hollywood to seek fame and fortune. While he was there, he met and befriended many of his heroes – and then, wound up acting in a film by his hero, another gentleman from Wisconsin: Orson Welles. That’s the situation Joseph McBride found himself in, starring in a “home movie” (but not the last Orson Welles movie, despite the press) along with John Huston and Peter Bogdanovich: The Other Side of the Wind. However, like so many Welles projects, ill fortune waited. The film was presumed lost for almost a half century, before Netflix – to their eternal credit – decided to try and piece it back together. McBride, for his part, stayed busy, developing one of the most unique resumes imaginable. Through Roger Corman’s production he acted in Hollywood Boulevard, starring Paul Bartel and directed by Allan Arkush and Joe Dante. He later co-wrote the Ramones movie, Rock ’n’ Roll High School, and grew into one of the most eminent Hollywood biographers ever, having produced biographies on such figures as Steven Spielberg, Frank Capra, John Ford, and – most recently – a critical study on Ernst Lubitsch, How Did Lubitsch Do It?, a gorgeous book which has drawn well-deserved rave reviews. In his spare time, McBride found the time to make several important discoveries in the Kennedy assassination investigation, as well as writing one of indispensable works in that field, Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J. D. Tippit.  The McBride shelf at the Green household. The McBride shelf at the Green household. It was the latter book that made him a natural to participate in a project that I had been hired onto – a film (Dallas in Wonderland) and accompanying documentary (King Kill 63). We flew Joe out to Dallas to walk the scenes of the J. D. Tippit murder and other important Dallas locations. We also, naturally, took the opportunity to talk films and filmmakers whenever we could. We were sitting around near Dealey Plaza when I asked him about one of my favorite directors of all time. JOE G.: So how do you like [Michelangelo] Antonioni? JOE McB.: He’s kind of pretentious. JOE G.: Sometimes I like pretentious. Which will help explain the last question of this interview. The Other Side of the Wind, and two accompanying documentaries - They'll Love Me When I'm Dead and A Final Cut for Orson: 40 Years in the Making - all drop on November 2. JOSEPH GREEN: Welles once said that Citizen Kane was, I quote, "an attack on acquisitiveness." And he was asked, “Did you intentionally put that in there?" And he said, "Well, I'm primarily a storyteller, but, yes." Although Kane is not a Leftist or Marxist critique of what you might call monopoly capitalism. So you can have these sorts of criticisms without necessarily adopting Marxist language or a Marxist point of view. JOSEPH McBRIDE: Well, he was never a Marxist, but he was very progressive. He was very...Leftist in those days especially. He was throughout his entire life, but he was very outspokenly on the left at the time. There's a good book on Kane by Laura Mulvey for the British Film Institute BFI Classic Series. It goes into the politics of Kane quite a lot, which I think has been sort of neglected because it is a real attack on fascism and on people like Hearst and domestic tyrants. What that whole kind of tyrannical personality entails, in terms of their personal and their public lives. [Joe just sent me a note about his answer to this question about Welles and leftist sentiments which reads as follows: "And when I say Welles was never a Marxist, I wonder if that was right. He was accused by the FBI of being a Communist, which he never was. But his work has some Marxist influence. If asked again I might like to quote what Lee Oswald said when asked if he was a Communist or a Marxist: “No, sir, I am not a Communist . . . Well, I have studied Marxist philosophy, yes, sir, and also other philosophers. . . . Well, I would very definitely say that I am a Marxist, that is correct, but that does not mean, however, that I am a Communist.” Which is a good example of how one interest can inform another.] And even what are now sometimes called false sponsorship or false flag operations, I mean, in some sense. False flag? Like in the famous line where he says… Ah! "You furnish the pictures and I'll provide the war." Yes. And that was actually taken directly from Hearst's life. There was a famous exchange of telegrams with Frederic Remington, the great artist, who was doing drawings for him in Cuba and they cooked up the Spanish American War with the false flag sinking of the Maine, etc. There were some things in the script that were more overtly political than Welles was allowed to put in the film. For example, Hearst was accused of encouraging the assassination of McKinley because one of his papers actually called for McKinley to be shot. And then when he was shot by an anarchist, Hearst got a lot of publicity for all that. Welles had that in the film and they cut it out. The film’s editor Robert Wise told me that they showed Kane at Radio City Music Hall when Hearst was trying to stop the film. Welles showed it to the lawyers and executives of all the corporations that ran the movie business, so they could make a decision on whether to shelve the film or let it come out. Wise said that this was Welles's greatest performance. He gave a very passionate speech about fascism and how it was taking over Europe and we had to stop it. And so suppressing the film would be giving in to that fascist impulse. Welles’s very powerful speech worked – they released the film, but they made him cut things out and Wise told me he spent five weeks recutting it. One of the things that went was the blaming of Kane for the McKinley assassination. There's a little allusion to it in the film. It's at one point in the newsreel; it's sort of incoherent at that point because they made some cuts. That's just one example. But it has a lot of pretty overt political references. I mean you see Kane with Hitler, for example. Well, and Welles maybe met Hitler. I was gonna ask you about that, too. He did know Churchill apparently. How much truth was in those stories? He claimed that as a boy in 1929, he met Hitler in a Munich beer hall. Pat McGilligan's Young Orson tried to track down all these stories. It may be one of these stories that you can't prove or disprove. But he claimed was in some beer hall and sat next to this guy and later realized it was Hitler. The thing that Pat told me was - he's a very good researcher - is that a lot of the stories that people thought Welles made up turned out to be true. Like he claimed that he was a bullfighter and everybody thought, "That's absurd." But then he found out Welles had been a bullfighter briefly and he was able to get proof. He said most of the stories Welles said were true. And that, the fistfight with Hemingway and, you know, those are… You know that actually happened. It boggles the imagination to have had a life like that. Yeah, well that's part of Pat's - Have you read Pat's book? It's really good. I have not, but I'm going to now. I helped him with some research and, but he did prodigious research on Welles's youth and nobody'd ever looked into his parents, for example, who were both amazing characters and his very unusual childhood. And then the whole theater and radio days. It goes into detail on all kinds of these amazing stories. And Pat said that basically he found that Welles just had an extraordinary life, and a very privileged one. I mean, he was privileged because the family was wealthy and his father and mother both introduced him to a lot of people in show business. Then he traveled widely, and he got into all - he was a very daring and adventurous young man, so he got into all kinds of situations. The idea that he would direct the black Macbeth at age 20 in Harlem is pretty astonishing. And the black actors and crew people all became very devoted to him even though they had some quarrels. But the chutzpah of a 20 year old guy doing that is astonishing. [Orson Welles directed a theatrical production of Macbeth featuring an all-black cast – rather ingeniously resetting the play from Scotland to Haiti. This was in 1936. – editor’s note.] Yeah it is. It is. And speaking of that sort of thing. I was trying to think if there were precursors or if there's any - had anybody really attempted something like Chimes at Midnight? [Joe does a commentary on the recent blu-ray edition of the film.] Uh, rewriting Shakespeare, sort of. Well, there's been so many Shakespeare films, um... You know, I mean, there was even a silent Shakespeare with Sarah Bernhardt in it. But when they did silent Shakespeare, obviously they were pretty loose in their rendering of it. But Welles was trying something very ambitious by combining several plays in one. He had done that as a young man at the Todd School. [The Todd Seminary School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois.] As a boy at the Todd School, he did Richard III and he combined various plays. And then in 1939, he did a big production called Five Kings, in which he played Falstaff and it was kind of the precursor to Chimes at Midnight. That was a famous disaster because it was too ambitious and too long and technical things didn't work out and they lost a lot of money on it. That's one reason he went to Hollywood – he needed money after that debacle. But he did Chimes of Midnight onstage in Ireland as a kind of rehearsal for the film. So it is quite astonishing what he did combining these things. And he took a very free approach to Shakespeare. He did that in his early days as a stage director, too. He would freely cut Shakespeare or even take lines from different plays and put them in some other play and, you know... There was an old joke at the time that one of the actors in one of those plays said "When is this ever gonna come out?" And the guy said "When Orson finishes writing it."

for Shakespeare and taken seriously in that regard. And I don't know that there is another American actor like that today. Is there? Well, there were people like Maurice Evans and the Barrymores. There were Americans who did a lot with Shakespeare, but Welles had a very cosmopolitan personality. I think that made him unusual in that he was really a man of the world, even as a boy. He was not purely an American figure, although many aspects of Welles are very American. I mean, he was actually blacklisted and that's why he was in Europe from '47 onward and came back in 1970. So, he was like a European art film director in a way. Part of my book, What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?: A Portrait of an Independent Career, part of the thesis, which I borrowed from Douglas Gomery, who's a very good film historian…he and I went to college together…he said that Welles was always an independent director even when he was working at RKO. He was, as Doug put it, he briefly was using the resources of a major studio but remained an independent director from the beginning in the sense of doing it his way and breaking new ground. So when he goes to Europe and left Hollywood behind, he embraced his avocation as an avant-garde director. But then he always was; I mean, Kane is a very avant-garde film. As are many of his films. In some cases, creating genres, like F for Fake. Even The Lady From Shanghai, for example. It’s a genre film that's very bizarre and very adventurous. So, throughout his career, he was independent and then, later, when he left the studios behind altogether after Touch of Evil, he was literally a home movie maker. He was making movies in his home and he was doing them with his own money mostly. And he was just doing just what he wanted, shooting film all the time. That's one thing people don't realize about him – he was always working. When he died, The New York Times said in their obituary he had been inactive as a director for the past several years and they had to retract that because it wasn't true. I met him in 1970 and I knew him until the end of his life in '85. And I worked with him for those 6 years on The Other Side of the Wind and I think one reason he put me in the film as an actor, aside from the kind of serious young film buff that I was, was to have a historian on the set because he was frustrated by a lot of false reporting out of his films. There were a lot of mythical tales spun about his work and so, here was somebody he knew that was a reliable historian who could report on what was happening. And I'm in a new documentary that's being made called They'll Love Me When I'm Dead, which is about the making of The Other Side of the Wind and also about that whole later period of his days in Hollywood before he died. And, so I'm using that experience as an on-the-set historian to share with the man who's making the film, Morgan Neville, and, he's the guy who made a fine documentary on William F. Buckley and Gore Vidal. You may have seen it. Oh, yeah, that's a great documentary. [Best of Enemies, which I reviewed on this blog. Neville also had a great success this year with the documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor?] Yeah, that's wonderful. Morgan is doing this really interesting film…Welles often would call me over and explain what he was doing or tell me where he had got the idea for certain lines or scenes and explain the background of things. And I think he was doing that on purpose so I'd pass it along. So that was part of what I was doing back then. I was an historian while these people were still around and I was very fortunate when I came to Hollywood that most of the great directors who I wanted to meet were still alive and available. I realized when I was putting Two Cheers for Hollywood together that I've been writing about 50 years exactly, because I sold my first film article in 1967 to Film Heritage magazine. Although "sold" is a euphemism because I didn't get paid for a couple years…but I started getting published in Film Heritage. I should say Film Heritage was edited by Tony Macklin, who I'm grateful to for getting me published, and then Ernest Callenbach the editor of Film Quarterly, brought me in and said, "I like your work. Would you write for us?" I started writing for them. So I was, for a while, writing for several film magazines. I was very ambitious to get things published when I was starting out and writing all kinds of articles, six, seven a year in these magazines. I was also doing my book on Orson Welles, which started in '66 because I'd seen Citizen Kane in a film class in September 1966 at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and that got me interested in a life in film. I wanted to write about film and make films. So I started writing a book on Kane, and somehow I managed to borrow a copy of the film on 16 millimeter, and I watched it over and over. I've seen it over 100 times now- Fantastic. [Citizen Kane] was my cinematic textbook – along with the script, which I found at the Wisconsin Historical Society. They had a copy of the script, so I went there with my portable typewriter for a month and typed an exact copy because I couldn't afford to Xerox it. So, I was teaching myself how to write screenplays and making short films... Then, after a couple years I realized Welles had done so many good films and there wasn't a good book in English on him, and I should expand [the book] to his entire body of work. I finished that in 1970 and then I did my book on John Ford with Mike Wilmington, which came out in 1974 although we finished it in 1971. It took three years to get published because those first two books were published in England by the British Film Institute and Secker & Warburg. The Welles book was picked up by Viking in the US, Viking Press, which was my publisher. Big publisher. I heard it sold 15,000 copies, although I never got any royalties at all from that. Secker & Warburg cheated me. Finally, after about 20 years I made a settlement with them and got the rights to the books back and we got the Ford book. The point I was going to make was that Ford was so out of fashion in America that no American publisher would publish it. Wow. The publisher was using that as an excuse to not put it out in England. I saw in the contract there was nothing that says all this is contingent on having an American publisher, so I actually went to London and walked into the office and demanded the book back, and they got the book published but by then Ford had died. It could have been two years earlier. Anyway, that's what I was doing in the early days. So, some of this book goes back to some of those earliest articles that I wrote, and some that Mike and I did together. For example, the Swedish film The Emigrants and The New Land, two different films, were being made in Wisconsin. I said, "Let's get on the bus and go find them." So we got on the bus one Saturday and drove out in the countryside and found the filmmakers doing this film with Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann. That was the first film I'd ever seen shot, so we wrote about that in Sight and Sound, and they were delighted to get the article because it was so unusual, you know? That was one of my tricks I found out. The other with Sight and Sound, David Wilson, who is another one of my editors. He said, "When a Bergman film comes out, we have 50 essays on him. We probably will run one. But when you send in something, nobody else in the world has thought of doing it, so we'll always run your stuff." That was part of my success – thinking of unusual things. I would interview directors, for example, who were kind of unknown or unappreciated, for example, Richard Lester, who I always admired a great deal. People loved A Hard Day's Night and Help! and other films, but he had made The Bed Sitting Room, which is a fascinating apocalyptic, absurdist comedy. I liked it a lot but hardly anybody in the world saw it…I went to London in '72 and just picked up the phone and called him. He answered and said, "Come on over." That's probably my favorite director interview in the book. We really had a good rapport. He's such an intelligent man. It's really a delight to read it.  Joseph McBride on location at the Texas Theater in Dallas on the King Kill 63 shoot Joseph McBride on location at the Texas Theater in Dallas on the King Kill 63 shoot Yeah, it's great. It was somebody that I wasn't expecting to find in the book [Two Cheers for Hollywood: Joseph McBride on Movies]. Of course, I come in much later on that. So, because when I was a kid, for a while Superman II was my favorite movie. Oh, yeah. I prefer the Lester version. They recently came out with a Donner cut, which basically takes out the humor. Yeah. Lester is essentially seeing this as, this is basically ... A superhero movie is essentially comic. Now they’re taken very seriously, which is ridiculous. It’s fine. But I think Lester’s take is right on. He loves to satirize genres, too. He was one of the directors who was doing that post-modern, satirical approach to genres back then. Well, sure. That John Lennon picture he made, that was sort of favorable towards Germany… No, I wouldn't say that, How I Won the War? Yes. Well perhaps I shouldn't say that it was favorable towards Germany, what I mean is it dared to treat the German people as people, I would say. Recognized their humanity. Yeah, and it also mocked Churchill and other pretensions of the British upper classes. He was a real iconoclast and that's one reason people liked him. He would get people upset because he had a puppet of Churchill in How I Won the War that kept saying, "I want a battle! I want a battle!" Right, yeah. So there must be miles of footage of The Other Side of the Wind extant. Well you know one thing, you and I may have talked about this with Randy [Benson], that's a ...he put out that set [of his film The Searchers] and I bought it, which was the uncut interviews he did for the film, which was...I mean it's a really valuable set, because you have people like Mark Lane and John Judge, who are no longer with us. So you could do that with your raw materials [for King Kill 63]. You had so many good people on camera, and it would be valuable. I want to propose that for The Other Side of the Wind, by the way. I have this crazy idea that we should put all ninety-six hours of the raw footage out, just as a special set for super Wellesian buffs, so that you could just look at everything he shot. And you could also...I could see film students reconfiguring and remixing the material, too. Yeah, there's some of that going on. You know that film, Too Much Johnson, which I wrote about in Two Cheers for Hollywood: Joseph McBride on Movies. That's online, because it was a Welles film that was rediscovered and it's in the public domain, but it was the rough cut. Various people have done cuts of it, but Eastman House has the material, they're preserving it, and they put the raw material online, which I thought was great, because they didn't try to re-edit the film. There was a guy named Scott Simmon who did his version, and then Bruce Goldstein of the Film Forum did a version with an editor. And I actually kind of advised them on that, and we had a lot of fun doing it. So you can edit that film in different ways. As long as you don't claim it's Welles' cut, as long as the original doesn't get thrown away or anything like that. Did Welles shoot the whole picture? Of The Other Side of the Wind? Well he shot everything but two shots, as I understood. [Actually, a few more special-effects shots had to be added by Industrial Light & Magic]. I asked Gary Graver, his cameraman, and…there are two shots he didn't do [at the end]. One you see from a distance smoke rising from a crash. They need to shoot two things. [There’s a] drive-in where they were shooting [the last scene], but it has been destroyed. It no longer exists, so they'll have to recreate it somehow on CGI, but that's not hard to do now. There’s some irony there. His films were forever being reconstructed by others even when he was alive. The Magnificent Ambersons – I think they took like three reels out of it, right? They took fifty minutes out of it, roughly, and then they re-shot parts of it. One of my dream projects, which I've been thinking of for a number of years and I've been making some headway on. I want to go to Brazil and look for the missing print. Welles had a print down there which was thirty-one reels of film, which is a lot of stuff. There were rumors that he left it behind because he went down there with the rough cut and some additional reels of material and he and Robert [Wise] were supposed to finish editing the film. Wise was supposed to come down there, then the studio reneged on that. They blamed the fact that...there was a war on, you couldn't get a plane. I don't know if that's the real reason, or not, but they were cutting the film back in Hollywood, and Welles would send cables and make phone calls that they were ignoring what he wanted to do. But he had this print, and at a certain point...Well in December of '42, RKO had destroyed the negative material that was cut. But the material he took down there could still be floating around Brazil. This is the rumor, anyway. And as late as 1944 there is some indication that it was maybe at the Rio de Janeiro office of RKO, and I don't know why Welles didn't take it back with him, except that it was hard for him to get back to Hollywood. It took him like two months just to get himself back. He was working for the US government partly as a diplomat, doing goodwill speeches and things. So he did some shooting and it fell through, and then he flew back in little planes. Maybe carrying thirty-one cans of film might have been impossible. But there was a rumor that he may have left it with a guy who owned a film studio down there in Rio, who was a film buff, collector guy. A friend of mine, Bill Krohn, who co-directed the documentary It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles, theorized that Welles might have given it to him, and it might be in that company which still exists. The man's daughter now runs the company. Bill actually checked, and she didn't think they had it, but you know how film labs and film companies sometimes don't know what they have. So I want to go down there, and I have a couple former students who are resilient, and I want to make a little super cheap documentary of me looking for the film. Kind of like Raiders of the Lost Ark. Even if the film can't be found, I really want to make an effort to see if it can be found. And stranger things have happened. Like The Passion of Joan of Arc, the original prints showed up in a Danish mental hospital in the early eighties. And then Metropolis, they found a print in South America that was 30 minutes longer than the one we have, and so it's conceivable the film might be down there. And I want to make the effort. I'm going to do it, it's just a question of when. I was invited to a film festival in Rio a couple years ago, and I was pretty sick at the time. I had been traveling a lot, but I realize I could only...I had like two or three days to look for it, that's not good enough. I'd have to go down there for at least three weeks and just really have time to plan the whole thing. So I'm going to try to make that happen once I get free of these other books that I'm working on. [McBride did a half-hour video interview for the November 20 Criterion Collection Blu-ray edition of The Magnificent Ambersons on RKO’s mutilation of the film and Welles’s firing by the studio.] That sounds brilliant. How does it feel to have finally seen the The Other Side of the Wind on the big screen? Was it what you expected?

After the American premiere at the Telluride Film Festival in August, I was on a panel with Frank Marshall and Peter Bogdanovich. Peter said it was a very sad film, which it is, and said he felt it was the end of everything. Frank said he felt bittersweet about its completion, since he’d been hoping to complete the film for almost fifty years and although he felt a great sense of accomplishment, he wondered what he would do now that it is finished. When I pondered my reaction, I thought of what Hemingway said, that you have to think hard about what you really feel and not what people expect you to feel. I realized what I really feel is that we had all pooled our talents and hard work to help realize Orson’s vision. As members of VISTOW (Volunteers in Service to Orson Welles), we had been part of the greatest creative endeavor in our lives. So I don’t feel sad or bittersweet but how a marathon runner must feel winning a marathon — the triumph of finally getting over the finish line. And the film itself is even better than I had thought it would be, and I always believed in it and fought to get it completed as a feature, not as part of a documentary, as some (including even Welles) had suggested doing at one time or another. Welles had a history of getting his films taken away from him and re-edited. For The Other Side of the Wind, the editing took place for artistic reasons, by people who care about his work. Would Welles have been pleased by the result? I think he would, since it follows the editing and stylistic template he established in the parts he did put together. The rest is a dedicated attempt to honor that vision. And the people who finished it felt a strong sense of responsibility to do it well. I have a few reservations about the final result, but that’s inevitable. It took a team to finish it, and no one, no matter how admiring of the material, would have exactly the same view of the final result. I always knew some people who like it and some would not. And without Orson here, it’s not exactly how he would finish it. But in many ways that’s an idle question, since he constantly reevaluated, rethought, and even reedited his own films, so who knows what he would have done with this material in 2018? He always evolved artistically. But I believe he would be proud of the final result and grateful to Bob Murawski for his editing and to the producers for their yeoman work. Last question: Would Antonioni have liked the film? Perhaps not, but it’s ironic that he is such an influence on Welles’s film, both in the parody of Zabriskie Point and in the strange similarities between The Other Side of the Wind and La Notte, which also deals with one night at a drunken party that represents a civilization in collapse. Welles’s editing is definitely more active and propulsive than Antonioni’s generally languid style, which Welles detested. But Welles, despite himself, was influenced by Antonioni. Antagonism is partly based on attraction or what Hitchcock called attraction/repulsion.

0 Comments

There is a new report from the UK newspaper The Independent which states that the Pentagon paid a public relations firm $500 million to produce anti-Al Qaeda propaganda films. Half a billion dollars. These films were aimed at insurgents. Bell Pottinger was first tasked by the interim Iraqi government in 2004 to promote democratic elections. They received $540m between May 2007 and December 2011, but could have earned as much as $120m from the US in 2006. In case you were unaware, the United States government created, trained, and funded Al-Qaeda ("The Base"), including alleged 9/11 mastermind Osama bin Laden. www.theguardian.com/world/1999/jan/17/yemen.islam This was confirmed by Zbigniew Brzezinski himself, who boasted about it in 1998: Question: The former director of the CIA, Robert Gates, stated in his memoirs that the American intelligence services began to aid the Mujahiddin in Afghanistan six months before the Soviet intervention. Is this period, you were the national securty advisor to President Carter. You therefore played a key role in this affair. Is this correct? The United States government created and funded a terrorist group. That terrorist group was then blamed for attacking us on 9/11, although their attacks also had the benefit of bringing down two buildings which were full of asbestos and one building which was full of records related to the CIA and several SEC investigations. It also had the benefit of making everyone forget about Donald Rumsfeld's remark that the Pentagon had misplaced $2 trillion the day before, and of course funded any number of domestic military projects, thus pouring money into the coffers of Halliburton, Raytheon, etc. Then they took $500 million over a four year period to finance videos opposing the terrorists they created. What good could half a billion dollars have done in our own country, applied to something useful, like say infrastructure or food? I know, it doesn't work like that, I'm a crazy leftist. But doesn't it at least seem slightly odd? Not really. After all, Israel created both Hamas and Hezbollah. So this is just business as usual: create your enemies, then fight the enemies you created, then #winning. Ok. |

AuthorThis is Joe Green's blog. Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed