|

Still don't know when the hell we'll ever get distribution, but I found some stills to give some idea of the speaker list.

0 Comments

Back when the MadLab theatre group out of Columbus, Ohio, staged an award-winning production (a revival, as the world premiere happened at the Overtime) of my play Clowntime is Over, the director/actor Andy Batt sent me a few questions to answer. I did my best to answer them. (Note: this Q&A took place in August of 2015.) ANDY BATT: Do you have any personal feelings about clowns, llamas, bunnies, mice, or snakes that you feel we should know about? JOE GREEN: Yes. I love bunnies more or less like an eight year old. Llamas are generally amusing, and the snake...to reveal that story will give away plot points in the play. However, someone very close to me had a snake (which I had named Pancakes despite the snake already having a name) that inspired that element. This play has a lot of religious as well as scientific ideas and philosophies floating around in the text. Do you identify yourself with any specific religion? Atheist or Agnostic? I became an atheist around age 12 or so and stayed that way for twenty years. I would lean agnostic these days. I studied Western philosophy from a young age and am reasonably familiar with its major tenets and movements up until Wittgenstein, where in my opinion things got a little derailed. But that's a long story. You also touch on a lot of historical psychiatry. Do you have a love of psychiatry? If so, where does that come from? Tell me about your mother. Nice. No mom issues here! I am familiar in a casual way with psychology but am in no way expert. Jung is an important thinker to me, but almost every writer or artist will say that. What was your initial inspiration for the play?

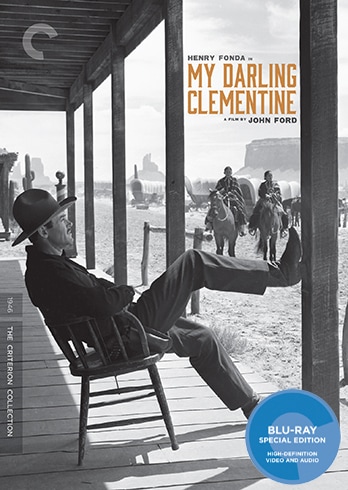

One of my best friends is Michelle Mezzone, for whom the play is dedicated. We were talking one day about a television show she used to watch in the Pacific Northwest that featured a clown, and as she was describing it to me the first act of the play more or less appeared in my head. That doesn't happen very often - very little of my life directly comes into my plays, except this one. Which might be why it's my favorite of the ones I've written. Who is your favorite playwright and why? An impossible question. I love so many modern playwrights - Shanley, McNally, Mamet, Durang, Kushner, Guare, and of course Beckett and Ionesco and Stoppard and Robert Bolt. I do gravitate more to post-Beckett playwrights than, say, O'Neill or Williams. I actually kind of dislike Arthur Miller. Very difficult question. What is your favorite play and why? Jesus. Probably the play I've read more than any other is Richard III for the sheer pleasure of the words. I could go Travesties, by Stoppard. Speed the Plow or Glengarry, Mamet was at his peak then. Danny and the Deep Blue Sea, and this one thing - a little one act where these two kids fall in love that Shanley did that just knocks me out every time. [I didn't remember the play at the time, but it is The Red Coat.] It's a really hard question and hope I didn't bore you with the answers. Also - I'm a pretty big fan of Clowntime.  When I was about eleven years old, I received a Leonard Maltin book as a gift: a thick paperback movie guide full of capsule reviews going from 1983 to The Birth of a Nation. I carried that thing around everywhere for a while, like a teddy bear. I also read it not like a reference book, but rather front to back, because nobody said, hey stupid, that’s not how you read a book like that. The book opened up a world of making: actors, directors, writers, and producers, from Ida Lupino to Howard Hawks to Akira Kurosawa. Soon, the first journal I ever kept was filled with my own reviews and thoughts about then-contemporary pictures like War Games and the films of John Carpenter. It started my love affair with movies -- seeing them, thinking about them, writing about them -- that still burns, only a touch less hot than then. That love affair also drives San Francisco State University professor Joseph McBride, and his new book is a vast, stunning exploration into filmmaking, criticism, and legend. Two Cheers for Hollywood resembles its author in being difficult to summarize due to its incredible scope. McBride, in addition to working as a journalist for entities like The Nation, has written definitive biographies of Frank Capra, Steven Spielberg, John Ford, and Orson Welles, has made major discoveries in the JFK assassination, acted in the “lost” and final Welles picture, The Other Side of the Wind (rescued by Netflix for future release), and co-wrote the Ramones movie, Rock and Roll High School. He's racked up endorsements, including from director Guillermo del Toro. (And it continues: up next, a critical study of the great Ernst Lubitsch.) In the course of this nearly 700-page book are interviews including everyone from Francois Truffaut to Richard Lester to Gore Vidal to Peter O’Toole, and many others, some with names less familiar. For example, one of the most fascinating interviews is with John Lee Mahin, who was a budding playwright when his friend Ben Hecht said he and Charlie MacArthur were going to Hollywood. Mahin agreed to tag along, and embarked on a life of writing pictures for MGM – one of his first jobs was fixing the dialogue on a little movie for Howard Hawks called Scarface. It is, at least in part, these sorts of details that form the subject for much of this book. How does Hollywood work? How do good pictures get made? How does any picture get made? And in between the rain drops, as it were, are the thousands of observations and interesting facts that make up the text of Two Cheers for Hollywood. Another example: The director John Huston made a terrific adventure film called The Man Who Would Be King, based on Kipling, despite his own qualms about the colonialist point of view of the source material. He also notes that, in casting, the picture had been offered to Paul Newman and Robert Redford, hot off the success of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, but Newman himself felt the lead characters should not be Americans. Indeed, Sean Connery and Michael Caine are perfectly cast in the finished film. (And, many years later, Robert Redford would play an Englishman – an Englishman who just happens to be from that part of England where people have the exact speech pattern as Robert Redford – in Sydney Pollack’s Out of Africa.) Films featuring commentaries from author Joseph McBride As an interviewer, McBride proves again and again to bring excellent questions to bear -- although John Ford hilariously disagrees in an early interview. However, as an essayist there are moments here that are nothing short of extraordinary. In a piece written for the New York Review of Books, McBride tackles director James Whale’s life as reflected in the media, particularly Father of Frankenstein, Christopher Beam’s literary take on Whale, and the subsequent film Gods and Monsters with Ian McKellen and Brendan Fraser. Whale directed such films as Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, and The Invisible Man, but after a certain point his career dissipated. Did his homosexuality play a role in Whale’s separation from filmmaking? Perhaps, although as McBride observes, “…it’s a known fact in Hollywood that when someone is already on the skids, everything seems to be working against him, and it can be hard to distinguish gratuitous snubs from root causes.” (358) Indeed.

McBride also delves into the film catalog of the Coen Brothers, and it is fascinating to read as he deconstructs much that is good and bad at their core. He contrasts their own Inside Llwellyn Davis with Christopher Guest’s A Mighty Wind, and points out that both films downplay the politics of the period. I entirely agree, and found fault with the Coen Brothers picture for utilizing the period without getting into the larger issues driving the behavior. Why use this backdrop if the Civil Rights movement will play not role? (In the Guest film, this was merely a continuation of his attitude at National Lampoon, where he helped write a skit making fun of earnest protest singers. Which is perhaps to be expected from Baron Haden-Guest.) He also chastises Miller’s Crossing for lacking the sense of humor found in their other work – and puts his finger on what might be the reason I always found it not quite satisfactory (the script reads better than the film plays). But this just scratches the surface. There is an excellent back-and-forth on Irish representation in John Ford’s The Quiet Man, an appreciation of the complexity of John Wayne’s screen image, a spirited defense of the more “serious” work of Steven Spielberg. This is a book to ponder and savor, a glorious treasury of cinema history. McBride has described his time spent filming The Other Side of the Wind with Orson Welles as a “Walter Mitty dream.” Two Cheers for Hollywood is Walter Mitty’s diary, a compilation of observations from a cinephile’s cinephile. Reading this book has given me the sort of pleasure I associate with my eleven-year-old self, when this whole magical world of filmmaking was first revealed. If you have any curiosity for film history at all, you must have this book.  A PDF version of an essay from my first book, Dissenting Views, about the mythology of science. In light of the recent science march - which I agree with in some ways - it seemed apropos.

|

AuthorThis is Joe Green's blog. Archives

August 2021

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed